One of my clearest childhood memories is the way my mum would lead my sister, our dog and me across the main street in the part of East London where our family lived. The process went something like this. Grasp your children’s wrists so tightly that their little hands turn pale due to lack of circulation, and shorten dog lead so much that dog is on hind legs. Adopt an expression of sheer panic, passing a feeling of abject terror to children and dog, which now thinks some sort of attack is imminent. Frantically turn your head from right to left so quickly that you feel dizzy. Wait until all reasonable gaps in the traffic have passed and then, when a suitably large vehicle is approaching, run into the road dragging the entire next generation of your family with you – along with its dog. When your eight-year-old son utters an expletive, threaten to tell his father.

Even in this distant, somewhat exaggerated view, it is obvious she had made an assessment of the situation that was flawed. But that’s what we often do, especially when under pressure, we come up with the wrong solution - it’s part of being human. The possibility of misjudgement by pedestrians is why so much is done in our towns and cities to try and control their movement. However, the density of vehicles and people in many areas is so high that as soon as the traffic stops the two almost blend. People cross the road between stationary vehicles: to get to the bank, the office, the other shops, the bus stop, the station – It’s like the incoming tide pouring between pebbles on a beach. Motorcycles filtering past vehicles and high cabs on lorries simply add to the danger and general confusion of the busy street. Pedestrian fences are erected to separate people from vehicles; but they only work up to a point. Crossings are installed; but in numbers, if traffic flow is to be maintained, that are barely adequate. Factor in the number and variety of vehicles that use the road and the whole thing becomes too demanding for any system to work completely.

Part of the solution is for pedestrians to treat the road as a killing ground. It helps to think about the efforts made to separate them from the railway, despite the fact that it is easy to predict the path of a train, and compare these measures with the situation on the road. When human flesh meets the front of a train it is often as a result recklessness or suicide. On the road, flesh and metal often share the same area and a vehicle can change direction at any time. Just think of the railway as a bacon slicer that meat is fed into; and the road as a chopping board. It’s probably no surprise, then, that every year in European capital cities 43% of road death involves pedestrians. But realistic help is at hand – help like none that has gone before - because this time the human factor is being removed from the equation. Now, vehicle manufacturers have the means to take significant steps towards solving the pedestrian problem.

Although vehicle front shape has gradually changed to meet a demand to make them more pedestrian friendly, other priorities have always dominated OEM design strategy. Up until now pedestrian safety, like emissions, seems to have been placed in the ‘if we must’ box while cost, occupant safety, performance and style (not necessarily in that order) sells cars and, understandably, go in the ‘customer/priority/we love you’, box. But technology in electronics (CAN/multiplexing etc) and the associated proliferation of sensing and sensor design are changing all that. While manufactures become less passive towards pedestrian safety, so do the options that they are able to offer.

Traditionally, passive systems have been similar to those protecting the vehicle’s occupants. Air bags that deploy on impact due to a detected change in speed over a certain magnitude are reacting in a way similar to ‘pop-up’ bonnets that rise on impact with a pedestrian. Although each is important, in fact vitally important, they only come into play after impact and when sensor information is evaluated. However, vehicles are now becoming more active in their sensing with RADAR (radio detection and ranging) and LIDAR (light detection and ranging) attempting to identify and track pedestrian movement prior to a collision. The possibilities promise the greatest breakthrough in pedestrian protection since the wheel clamp: collision avoidance through reliable driver warning and, hopefully, remote braking. Some pedestrian collisions, though, do not involve an impact that necessarily causes death or injury - but they do involve one that almost always results in death.

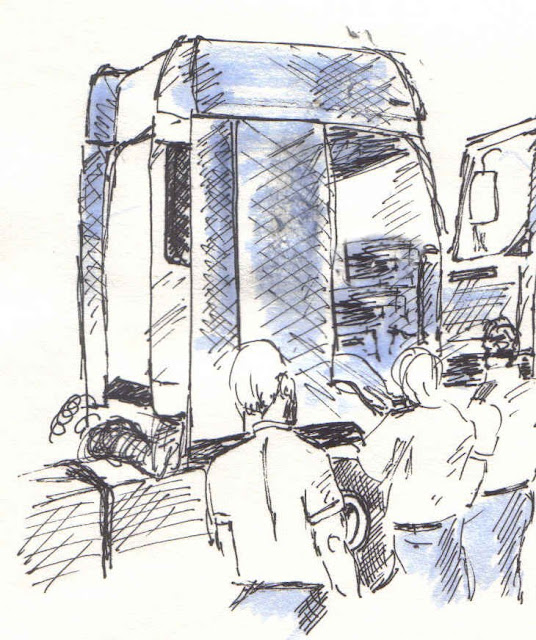

In slow moving traffic one of the most effective pieces of equipment in the ‘kitchen’ called the road has been the lorry – and in particular the high cab. A modern lorry cab is very tall, as is the drivers seating position. Many lorry drivers have to live in vehicles on extended trips, so a tall cab with a flat floor gives greater comfort, letting the driver stand up and move around more freely during rest periods. One way of achieving this is to raise the driver’s compartment above the height of the engine. The result is very high cabs. One answer would be to have American style trucks with bonnets, the engine positioned in front of the cab. However, in this country, as in much of Europe, the roads would not allow the extra length, so to be able to use a trailer of reasonable size tractor units have to be short. Tall cabs it is then - but what about pedestrians? The Elderly in particular with their failing senses are the most common victims of high cabs. In stop-start, queuing traffic, people can 'disappear' below the front of a high cab. Here, pedestrians are knocked over by the impact and then run over - the result is almost always death.

New legislation has seen the mandatory fitment of cab blind-spot mirrors that look down the front of the vehicle. Like all mirrors they rely on the driver actually using them – a check that is not always remembered. Mirrors are also only monitored periodically – no matter how short that period is. Once again, some form of sensing is the way forward (literally) when it comes to pedestrian detection, but this time, electronics might not be the only answer. It may be that Fresnel wide angle lenses, fixed to the lower part of the windscreen within the peripheral view of the driver, could be used to detect movement in front of the cab. Drivers would be alerted by movement in the lens, which would, in effect, warn them to look in the safety mirror.

New legislation has seen the mandatory fitment of cab blind-spot mirrors that look down the front of the vehicle. Like all mirrors they rely on the driver actually using them – a check that is not always remembered. Mirrors are also only monitored periodically – no matter how short that period is. Once again, some form of sensing is the way forward (literally) when it comes to pedestrian detection, but this time, electronics might not be the only answer. It may be that Fresnel wide angle lenses, fixed to the lower part of the windscreen within the peripheral view of the driver, could be used to detect movement in front of the cab. Drivers would be alerted by movement in the lens, which would, in effect, warn them to look in the safety mirror.

Whatever system is chosen, the need to take some of the responsibility away from the human participants in any collision should be paramount. By constantly monitoring and then reacting (faster than is humanly possible) active and passive systems should have great effect on reducing the number of pedestrian casualties on our roads. Machines controlled mechanically and not manually; systems with predictable results. It takes me back to the the kitchen of my childhood home. Next to the chopping board, we had a toaster - a machine programmed to put an end to charcoal and jam for breakfast.